Contrary to popular belief, metabolic slowdown after 35 is not inevitable; it’s a direct consequence of neglecting muscle, your body’s primary metabolic engine.

- Muscle tissue is a metabolically active organ that burns significantly more calories at rest than fat, directly influencing your basal metabolic rate (BMR).

- Age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia) triggers a cascade of negative effects, including reduced metabolic rate, bone density loss, and a dramatic increase in long-term healthcare costs.

Recommendation: Shift your focus from simple calorie restriction to a proactive strategy of building and maintaining muscle mass through targeted protein intake and resistance training to secure your long-term metabolic and financial health.

If you’re in your late 30s or beyond, you may have noticed a frustrating phenomenon: the scale creeps up even when your diet and activity levels haven’t changed. The common narrative blames an unavoidable, age-related metabolic slowdown, a force of nature to which you must simply surrender. You’re told to eat less, to accept a new normal of lower energy and persistent weight gain. This advice, while common, is dangerously incomplete. It overlooks the true culprit and, more importantly, the powerful solution within your control.

The passive decline of your metabolism is a myth. In reality, it is an active process driven by a critical factor: the progressive loss of muscle tissue. The real conversation isn’t about surrendering to age; it’s about understanding that your muscle is not just for strength or aesthetics. It is your body’s most significant metabolically active organ. Ignoring its health is like decommissioning your body’s primary furnace, leading to a predictable “sarcopenic cascade” of metabolic decline, bone fragility, and diminished vitality.

This article reframes the entire issue. We will move beyond the platitudes of “eat less, move more” to provide a scientific and urgent case for muscle preservation. We will treat muscle as a non-negotiable asset for long-term health. The true key to preventing metabolic slowdown isn’t a battle against your aging body, but a strategic investment in the very tissue that keeps your metabolic engine running hot.

This guide will dissect the science behind muscle’s metabolic power, provide actionable strategies for protein synthesis in an aging body, and reveal the stark economic reality of neglecting muscle health. Prepare to see your body not as a system in decline, but as a system you can actively command.

Summary: The Scientific Case for Prioritizing Muscle to Counteract Aging

- Why Muscle Tissue Burns More Calories at Rest Than Fat Tissue?

- How to Eat Protein to Trigger Muscle Synthesis When You Are Older?

- Cardio for Weight Loss vs. Muscle for Maintenance: Which Wins Long Term?

- The Sarcopenia Trap: What Happens to Your Bones When You Ignore Muscle Loss?

- Anabolic Window: Is It Real or Bro-Science for General Health?

- Why Sarcopenia Treatments Cost 3x More Than a Gym Membership Over 10 Years?

- Why Continuous Low-Intensity Movement Keeps Lipase Active?

- Investing in Physical Health: The ROI of Preventive Training vs. Medical Costs

Why Muscle Tissue Burns More Calories at Rest Than Fat Tissue?

The core of your metabolic rate—the energy you burn simply by being alive—is dictated not by your age, but by the composition of your body. Muscle tissue is fundamentally different from fat tissue at a cellular level; it is a metabolic powerhouse. The reason lies in an organelle you likely learned about in high school biology: the mitochondrion. Often called the “powerhouses of the cell,” mitochondria are densely packed within muscle fibers, constantly converting glucose and fat into usable energy (ATP). Fat tissue, in contrast, is primarily for storage and has a much lower mitochondrial density, making it metabolically quiet.

This structural difference has profound implications for your daily calorie burn. While exact numbers vary, compelling research shows that each pound of lean muscle burns roughly 5-7 calories per day at rest, whereas a pound of fat burns only about 2 calories. This may seem small, but losing ten pounds of muscle—a common occurrence during a decade of inactivity after 35—means your body automatically burns 50-70 fewer calories every single day, without you changing a thing. This deficit adds up to over 5 pounds of potential fat gain per year from metabolic slowdown alone.

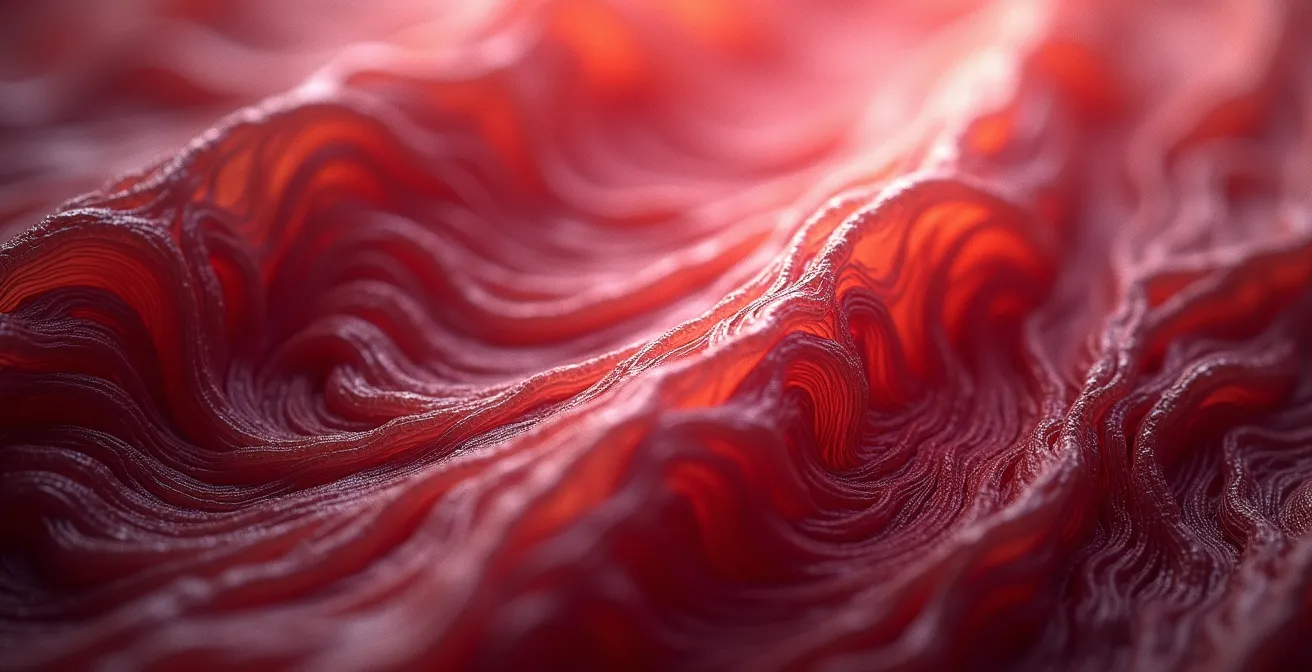

This slide illustrates why prioritizing muscle is a non-negotiable anti-aging strategy. The image below provides a conceptual look at the dense, active nature of muscle tissue, a stark contrast to the more passive fat tissue.

As you can see, the intricate structure of muscle is designed for high energy turnover. Studies on aging confirm that while mitochondrial *quality* can decline, maintaining muscle mass helps preserve overall metabolic function. It is the loss of the tissue itself, not just an inherent “slowing” of the mitochondria within it, that deals the primary blow to your metabolism. Maintaining this metabolically active organ is the single most effective strategy to keep your resting energy expenditure high as you age.

How to Eat Protein to Trigger Muscle Synthesis When You Are Older?

As we age, our bodies develop a condition known as anabolic resistance. This means our muscles become less responsive to the signals that trigger growth and repair, particularly from protein intake. The same serving of protein that easily stimulated muscle protein synthesis (MPS) in your 20s is less effective in your 40s. This isn’t a personal failure; it’s a documented physiological shift. In fact, specific research demonstrates that older adults show a 16% lower post-prandial muscle protein synthesis rate compared to their younger counterparts after consuming a standard amount of protein.

To overcome this resistance, the strategy for protein consumption must become more deliberate. It’s no longer just about total daily intake; it’s about the timing, distribution, and quality of that protein. The goal is to create strong, consistent pulses of amino acids in the bloodstream throughout the day to repeatedly “switch on” the MPS pathway. A single, large protein-heavy dinner is far less effective than distributing that same amount of protein across multiple meals. This approach ensures your muscles receive a steady supply of building blocks needed for maintenance and growth, effectively overriding the blunted anabolic signal.

This requires a conscious shift from a passive eating pattern to an active fueling strategy. You must think of each meal as an opportunity to combat sarcopenia. Prioritizing protein at breakfast is particularly crucial, as it breaks the long overnight fast and kick-starts muscle repair for the day ahead. Focusing on sources rich in the amino acid leucine—like whey protein, eggs, poultry, and soy—is especially effective, as leucine acts as a primary trigger for MPS.

Your Action Plan: Strategic Protein Intake to Overcome Anabolic Resistance

- Calculate Per-Meal Dosage: Consume approximately 0.25g of protein per kilogram of your body weight at each main meal to ensure you hit the leucine threshold needed to trigger muscle synthesis.

- Evenly Distribute Intake: Spread your total protein consumption evenly across 3-4 meals, spaced 3-4 hours apart, to provide a consistent anabolic signal throughout the day.

- Prioritize Breakfast Protein: Break your overnight fast with a high-protein meal (at least 25-30g) to halt muscle breakdown and initiate repair. Focus on leucine-rich sources.

- Consider Supporting Nutrients: Combine your protein intake with adequate Vitamin D and Omega-3 fatty acids, as they play supporting roles in muscle health and reducing inflammation that can worsen anabolic resistance.

- Assess and Adjust: Monitor your energy levels and recovery from exercise. If you feel constantly fatigued or sore, you may need to slightly increase your per-meal protein target to better support your body’s needs.

By adopting this methodical approach, you are no longer just eating; you are actively managing your body’s primary metabolic organ and fighting back against age-related decline.

Cardio for Weight Loss vs. Muscle for Maintenance: Which Wins Long Term?

In the quest for weight management after 35, many people default to cardiovascular exercise. The logic seems sound: running, cycling, or using the elliptical burns a significant number of calories, leading to a visible short-term impact on the scale. However, this approach has a critical flaw when viewed through the lens of long-term metabolic health. While cardio is excellent for heart health and immediate energy expenditure, it does little to build or even preserve your most valuable metabolic asset: muscle mass. In some cases of excessive, under-fueled cardio, it can even lead to muscle catabolism (breakdown).

The real game-changer for your metabolism is your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR)—the calories your body burns at rest. BMR is not static; it is heavily influenced by your body composition. Since muscle is far more metabolically active than fat, increasing or maintaining muscle mass directly increases your BMR. This means you burn more calories 24/7, even while sleeping or sitting at your desk. Resistance training is the primary stimulus for this effect. The calories you burn *during* a weightlifting session are often less than a long run, but the metabolic benefit continues for up to 48 hours post-workout as your muscles repair and rebuild stronger (a process known as EPOC, or excess post-exercise oxygen consumption).

This creates a powerful, sustainable cycle. More muscle leads to a higher BMR, which makes weight maintenance easier and creates a larger buffer against occasional dietary indiscretions. Relying solely on cardio for weight loss creates a fragile system where your weight is entirely dependent on your daily workout. If you get injured, busy, or lose motivation, the weight quickly returns because the underlying metabolic engine hasn’t been upgraded. The following table breaks down the long-term trade-offs.

| Exercise Type | Immediate Calorie Burn | Long-term Metabolic Effect | Muscle Preservation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardio | High | Moderate | Low |

| Resistance Training | Moderate | High | High |

| Combined Training | High | Very High | High |

The data is unequivocal. For sustainable, long-term metabolic health, a strategy that prioritizes resistance training—ideally combined with cardiovascular work—is vastly superior. It shifts the focus from “burning off” calories to actively building a more efficient, high-performance metabolic engine that serves you around the clock.

The Sarcopenia Trap: What Happens to Your Bones When You Ignore Muscle Loss?

Sarcopenia, the age-related loss of muscle mass and function, is not just a metabolic issue; it’s the beginning of a dangerous cascade that directly compromises your skeletal system. Muscle and bone are intrinsically linked in a dynamic relationship. Your muscles attach to your bones via tendons. When a muscle contracts during physical activity, it pulls on the bone. This mechanical stress is not damaging; it is a vital signal that instructs the bone to remodel itself and become stronger and denser to withstand the force.

When you neglect muscle health and sarcopenia sets in, this critical signaling process grinds to a halt. Weaker muscles place less stress on the skeleton, and the bones, receiving no stimulus to remain robust, begin to demineralize and lose density. This insidious process leads directly to osteopenia and, eventually, osteoporosis. You have now entered the sarcopenia trap: muscle loss leads to bone loss, which in turn increases fracture risk. A fall that would have been a minor incident in your 30s can become a life-altering hip or vertebral fracture in your 60s, leading to a cycle of immobility, further muscle loss, and declining independence.

This connection is not theoretical; it is a well-established physiological fact. As Robin DeWeese from Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions states, the evidence is clear: strength training is a direct intervention for bone health.

Strength training increases bone mineral density.

– Robin DeWeese, Arizona State University College of Health Solutions

Therefore, every session of resistance training is a dual-purpose investment. You are not only building your metabolic engine but also directly fortifying the structural framework of your body. Ignoring muscle loss after 35 is akin to letting the foundation of your house slowly crumble. By the time the cracks become visible, the damage is severe and far more difficult to repair. Proactively maintaining muscle mass is the most effective insurance policy against the fragility of aging.

Anabolic Window: Is It Real or Bro-Science for General Health?

For decades, fitness culture has been dominated by the concept of the “anabolic window”—a supposed 30-60 minute period post-workout where you must consume protein to maximize muscle growth. The fear of “wasting a workout” has led countless people to frantically chug protein shakes in the locker room. While there is a kernel of truth to this for elite athletes training multiple times a day, for the general population focused on health and preventing metabolic slowdown, this hyper-focus on immediate timing is largely misplaced energy. It’s a classic case of majoring in the minors.

Modern research has clarified the picture significantly. The process of muscle protein synthesis is elevated for a much longer period following a resistance workout, often for 24 to 48 hours. This means the “window of opportunity” is more like a “patio door.” For a person in their late 30s or 40s exercising for general health, the single most important factor is not *when* you consume protein relative to your workout, but your total daily protein intake and its even distribution throughout the day. A person who hits their daily protein goal, spread across three to four meals, will achieve far better results than someone who obsesses over a post-workout shake but falls short on their overall intake.

This is especially true when considering the reality of anabolic resistance in older adults. A consistent, steady supply of amino acids is more effective at stimulating the blunted muscle-building pathways than a single, large, post-workout dose. Focusing on the “anabolic window” can even be counterproductive if it leads to neglecting protein intake at other crucial times, like breakfast.

Case Study: Protein Timing vs. Total Intake in Older Adults

Comprehensive reviews examining protein intake patterns for muscle preservation in older, non-elite individuals have reached a clear consensus. Researchers found that while protein intake does enhance the muscle’s response to exercise, the benefits are primarily driven by achieving an adequate total daily protein amount. More importantly, distributing this total intake evenly throughout the day (e.g., 25-30g per meal) was shown to be a more effective strategy for stimulating muscle protein synthesis than concentrating a large dose around a workout. The key takeaway for the general population is to prioritize consistency and total daily goals over a narrowly defined “anabolic window.”

The verdict is in: for preventing age-related metabolic decline, the anabolic window is largely bro-science. Your focus should be on the strategic, day-long fueling of your muscle tissue, not on a frantic 30-minute sprint after you leave the gym.

Why Sarcopenia Treatments Cost 3x More Than a Gym Membership Over 10 Years?

Viewing a gym membership or a personal training plan as a discretionary expense is a critical financial miscalculation. This is not a cost; it is an investment that pays staggering dividends by preventing a far greater expense down the line: the medical cost of sarcopenia. As muscle mass and function decline, the risk of falls, fractures, and loss of independence skyrockets. This transition from functional health to managed fragility comes with an explosive price tag that dwarfs the cost of preventive exercise.

The numbers are alarming. As muscle weakness progresses, simple tasks become hazardous. Government health studies show that approximately 30% of adults over 70 have trouble with mobility, such as walking or climbing stairs. Each fall-related incident for an older adult can incur tens of thousands of dollars in emergency room visits, surgery, hospitalization, and rehabilitation. Furthermore, treatments for severe sarcopenia and osteoporosis, which may include long-term medication, physical therapy, and assisted living services, create a sustained financial drain. This is the “metabolic mortgage” coming due—years of neglecting muscle health result in high-interest payments in the form of medical bills and reduced quality of life.

When you compare these reactive costs to proactive investment, the return on investment (ROI) of a gym membership becomes undeniable. An annual gym fee is a predictable, manageable expense. The costs associated with a fall-related hip fracture or the long-term management of severe mobility issues are unpredictable and potentially catastrophic. Economic analyses of sarcopenia’s burden consistently show that the direct and indirect healthcare costs—including hospitalization, rehabilitation, and the need for home care—far exceed any investment in preventive fitness programs.

The choice is stark: pay a small, consistent premium now to maintain the metabolically active organ that ensures your strength and independence, or face the high probability of paying an exponentially larger, unplanned sum later to manage the consequences of its decay. It’s the ultimate financial and physical insurance policy.

Why Continuous Low-Intensity Movement Keeps Lipase Active?

While structured resistance training is the cornerstone of building and maintaining muscle, your metabolic health is also profoundly affected by what you do in the 23 hours outside the gym. Long periods of sitting—at a desk, in a car, on the couch—effectively switch off a crucial metabolic enzyme: Lipoprotein Lipase (LPL). LPL’s job is to pluck fat molecules from the bloodstream and shuttle them into cells to be used for energy or stored. When you are physically inactive, LPL activity in the muscles of your legs and back plummets, causing circulating blood fats (triglycerides) to rise, a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

The good news is that LPL is incredibly sensitive to even low-intensity muscular contraction. You don’t need a high-intensity workout to reactivate it. Simple acts like standing up, walking around your office, or doing a few bodyweight squats are enough to jolt this enzyme back into action. This is not about burning a significant number of calories; it’s about sending the right biochemical signals to keep your fat-processing machinery turned on.

The science on this is remarkably clear. Research from a pivotal study published in the Journal of Physiology demonstrated the dramatic effect of breaking up sedentary time. The authors highlighted the immediate impact of movement on this key enzyme.

Treadmill walking raised LPL activity approximately 8-fold within 4 hours after inactivity.

– Hamilton et al., Journal of Physiology Research

This finding underscores a powerful, actionable strategy: integrate frequent, low-intensity movement throughout your day. This practice of “exercise snacking” complements your formal workouts by keeping your metabolism from going dormant. By standing up and moving for just a few minutes every hour, you are actively managing your blood lipid levels and ensuring your body remains in a metabolically favorable state. It’s a simple, free, and scientifically-proven way to combat the negative effects of a modern, sedentary lifestyle.

- Take a 5-minute walk every hour during sedentary work.

- Perform light movements like squats or calf raises after meals to help process blood glucose and fats.

- Make a rule to stand and move for 2-3 minutes for every 30 minutes of sitting.

- Opt for walking meetings or take phone calls while standing.

- Consider using a standing desk for a portion of your workday to keep leg muscles engaged.

Key Takeaways

- Metabolic slowdown is not a function of age, but a direct result of muscle loss (sarcopenia).

- Muscle is a metabolically active organ; maintaining it through resistance training is the most effective way to keep your basal metabolic rate (BMR) high.

- The cost of treating sarcopenia-related issues like falls and fractures far exceeds the long-term investment in preventive gym training.

Investing in Physical Health: The ROI of Preventive Training vs. Medical Costs

The decision to actively combat metabolic slowdown is not merely a health choice; it is one of the most significant financial decisions you will make for your future. The prevailing mindset often frames exercise as a cost in time and money. The paradigm shift required after 35 is to see it as a high-return investment, protecting you from the catastrophic and often uninsurable costs of functional decline. The return on investment (ROI) isn’t measured in aesthetics, but in future medical bills avoided and years of independent, high-quality life secured.

Every dollar and hour you spend in the gym building and maintaining muscle mass is a direct deposit into your health savings account. This isn’t just theory; it’s a reality demonstrated by countless individuals who have reversed their metabolic age through dedicated training. Neglecting this investment is a gamble with grim odds, leading to what we’ve termed the “metabolic mortgage”—where the debt incurred by years of inactivity is paid back with interest through fall-related surgeries, long-term care, and a reliance on the healthcare system.

The financial comparison between prevention and treatment is brutally clear. A decade of gym fees is a predictable, manageable line item in a budget. In contrast, the costs associated with managing sarcopenia and its consequences are volatile and can be financially crippling. The table below, based on data from economic analyses of aging, quantifies this disparity.

This comparison from a comprehensive analysis of aging and healthcare costs highlights the stark financial choice between proactive investment and reactive treatment.

| Investment Type | Annual Cost | 10-Year Total | Health Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gym Membership + Training | $600-1200 | $6,000-12,000 | Prevents muscle loss, maintains independence |

| Sarcopenia Treatment | $3,000-5,000 | $30,000-50,000+ | Manages symptoms, may not restore function |

| Fall-Related Medical Costs | Variable | $35,000+ per incident | Recovery varies, potential disability |

The final analysis is simple. You can choose to pay a small, fixed price now for strength, vitality, and autonomy. Or you can defer payment and risk an invoice later that costs exponentially more in both dollars and quality of life. The most powerful lever you have to control your future health and wealth is the disciplined effort you put into preserving your muscle today.

Frequently Asked Questions on Protein Timing and Muscle Health

Do I need protein immediately after working out?

For recreational exercisers, the “anabolic window” is much wider than commonly believed, extending up to 24-48 hours after a workout. This makes focusing on your total daily protein intake and distributing it evenly far more critical than consuming protein immediately post-exercise.

How much protein should I consume per meal?

To effectively combat age-related anabolic resistance, aim for 20-40g of high-quality protein at each meal. This dose is typically sufficient to trigger muscle protein synthesis. Distribute these meals every 3-4 hours throughout the day for the best results.

Does the anabolic window change with age?

Yes, but not in the way most people think. For older adults, the importance of a specific, narrow post-workout window diminishes. Instead, the focus should shift to a more consistent and evenly distributed protein intake throughout the entire day to provide a steady stimulus for muscle maintenance and growth.